The Case of Reparations: A Justice or a Misguided Policy?

- kavieshkinger

- Feb 5, 2022

- 4 min read

It's April 13th, 1919. You stand amongst a crowd in Jallianwala Bagh in India to commemorate the harvest festival Baisakhi. An escape from the laborious days you are forced to repeat redundantly. An atmosphere of mirth envelops the crowd, as thousands dance in groups, a kaleidoscope of different people united under one celebration. Unbeknownst to you, the British authorities had recently prohibited such gatherings, an oversight that would have heinous repercussions. A pistol cracks. Gasps turn to screams. The defenseless crowd thins. A metallic aroma stains the air and you begin to flee. You turn around once more to see the rows of crimson coats that flank the entrance. An innocent celebration, now permanently tainted by the blood of the innocent, yet another atrocity to marr imperialism’s legacy.

Modern colonialism began at the start of the 15th century, to christen the ‘Age of Discovery’. An era born of greed. Greed for power. Greed for infinite wealth. Greed to spread their morals amongst the ‘barbarians’ in these foreign lands. Greed at the expense of the inherent rights of fellow human beings. First, the Portuguese began to seek new trade routes. Their rapid success in possessing territories in Africa, Asia, and South America, persuaded rival nations like England, Spain, Germany and the Netherlands to amass similar empires. Colonial powers justified their conquests by asserting a religious and moral obligation. They argued that their actions were of the best interest to the indigenous populations. But how morally just can one truly be to justify exploitation and oppression?

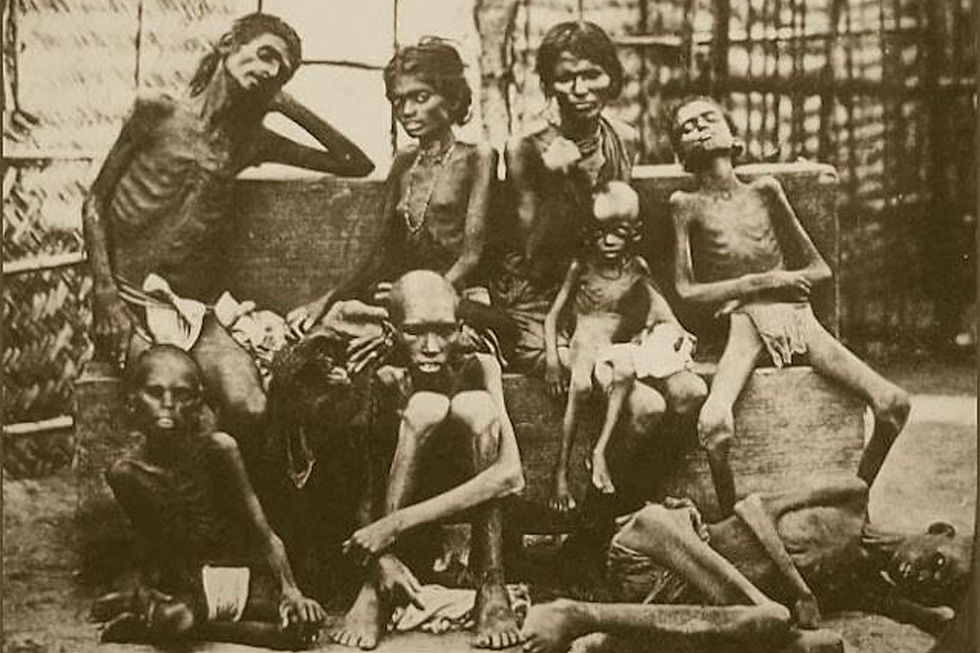

To emphasise the impact of colonisation, I would like to draw attention to colonial India. Before the advent of colonialism, India was a flourishing economy; a cornucopia of culture, technology, and knowledge. In fact, pre-colonial India occupied around 25% of the global economy, a staggering figure in comparison to their meagre 4% share after they gained independence from the British in 1947. At the same time, Britain's share of the world economy rose from 2.9% in 1700 up to 9% in 1870 alone. The British arrived in India in 1608, with the sole motive to paralyse the thriving nation by plundering their natural resources such as coal, iron ore and cotton. This includes invaluable national treasures such as the Kohinoor diamond from the venerated Peacock Throne, which was stolen and integrated into the crown jewels, an affront to the impoverished Indian population. More notably, the trauma endured by its citizens through cultural upheavel, social inferiority within their own homeland, and devastating genocides. For instance, the Bengal famine of 1943, which is estimated to have caused over three million deaths, resulted not from a drought as is widely believed but from the British government's policy failure. Essential crops were diverted away from starving civilians, and placed as reserves stockpiles to fatten the bellies of wealthy Eurpeans. Families were forced to watch their children wither away, dying at the behest of their colonisers, while revered PM Churchill reportedly asked “If food is so scarce, why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?”, reflecting the sheer apathy towards Indians. Dr. Shashi Tharoor, a member of the Indian parliament aptly summarised during his Oxford Union speech in 2015, “the sun never set on the British empire because even God couldn’t trust the Englishman in the dark”.

Similar atrocities were visited on the Congolese when in 1885, Belgian King Leopold II, seized the African region and established the Congo Free State, an ironic moniker that vastly contradicts the severe repression experienced by the native population. The King stated his aim was to bring civilisation to the Congolese, yet his reign was infamous for the methods of terror used to bring the populace to submission. Forced labour was used to gather resources such as rubber, palm oil, and ivory. The people of the Congo were often beaten as punishment, and lashings were used to force villages to meet their rubber-gathering quotas, as was the taking of hostages. Innocent children were no exceptions to this sadistic brutality. The population of the state dwindled from 20 million to 8 million, and those who evaded death were mutilated by having an arm or leg amputated. Arguably, the most heinous crime was the ‘human zoos’- an exhibition of suffering Africans kidnapped from their homelands to entertain ignorant European audiences. Around 267 Congolese were taken by force to Belgium and were displayed like animals in a zoo. This appalling spectacle decimated any hope for freedom from these individuals, along with entirely stripping their dignity and completely dehumanising them.

So, would former colonies be better off had they never been colonised? The legacy of colonialism is still very prevalent in society today. In these former colonies, there is a culture of Eurocentrism, an attitude that defines distinct binaries: Europe, a beacon of development and modernity, and the non-West, underdeveloped and traditional. In India, social bias against dark skin emerged which exemplified the caste system, which kindles an association between skin colour and societal status. Products such as ‘Fair and Lovely’ target lower socio-economic classes in South Asia, essentially profiting off their feelings of social inferiority. Similar ‘whitening’ tactics are evident in African nations- according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), 77% of women in Nigeria use skin lightening products. Moreover, this eurocentrism also highlights the economic disparity between these binaries. Countries with vast natural resources such as Africa and India, could have been superpowers, yet were rendered absolutely destitute after colonisers plundered their lands. As a result, colonialism has left independent nations unprepared to function in the modern global society and vulnerable to outside influence and pressures, while European countries used these stolen resources to modernise rapidly.

To summarise quickly: reparations are an ethical duty. A means of restitution to right the wrongs committed during colonialism. Historian John Mackenzie countered this notion, stating that “we should never impose the condescension of the present upon pastimes”, but then how do we learn from our mistakes and ensure that history never repeats itself? Besides, the UK was not hesitant to demand reparations from Germany after forcing them to accept the blame for the entirety of WW1- an extortionate amount of 132bn gold marks, with the final installment paid in 2010. Additionally, in 2008, Italy agreed to pay Libya $5 billion in compensation for its colonial past. Thus, reparations are not an outlandish concept. Rather it is an opportunity for former colonies to facilitate their recovery and development in this modern society. It is difficult to assign a value to justice, but the very act of discussing this policy can help truly liberate these nations from their nightmarish pasts.

By Desiree Menezes 12D

Comments